Working at Daisee, Jappie uses a lot of Haskell programming. Although Haskell is obviously as amazing as the stereotype asserts, the tooling can be a bit challenging. In this blogpost we explore these challenges.

One’s understanding start with the fact that there is not one unified Haskell package manager. Well there is, but only experts use cabal directly. The issue is that often dependencies don’t quite match from the Hackage repository, which cabal uses as repository. Loose version bounds within cabal configurations, cause one developer to develop against version 1.1 and another against version 1.2.

This is were stack stepped in. Stack guarantees that at some point in time all the provided packages in their repository will build together. They do this trough package curation and providing reproducible builds at least for Haskell packages. This is hosted on their alternative to Hackage, called Stackage.

Because of curation and being more restrictive, the stackage repository doesn’t host as much software as hackage does. In certain cases we may still need to configure stack in such a way that it pulls in a package or two from hackage.

System dependencies

Haskell is not an operating system. There is no Haskell Linux kernel or Haskell std lib. Therefore many Haskell libraries are dependent upon C code libraries. Stack does not include interaction with these system libraries as part of it’s reproducible build contract.

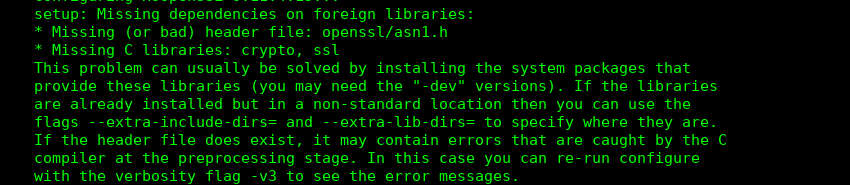

The user experiences this once stack starts requesting ‘devel’ packages, for example: Stack will request ‘ssl’ headers, and recommends the user to install a devel system package from his distribution package manager. It is up to the user to find the name of this system package for his respective distribution, in case of fedora it’s: “openssl-devel”, and in case of Ubuntu it’s “libssl-dev”. But gentoo wouldn’t even have devel packages, all packages in case of gentoo are devel packages.

Enter nix

Nix is also a package manager like stack and cabal are, however, it’s not focused on any specific language. Nix is about reproducible builds, eg guaranteeing some build on a developer machine is exactly the same as on the user machine.

A developer may for example have had the ssl library installed globally, but forgot to mark it as a dependency in his software package. A build tool would happily build that on his machine, but now when a user downloads this code and tries to build the package it will fail. Nix solves this.

In principle nix is completely independent from the Haskell ecosystem. Build around this package manager is even an entire distribution. But because it provides system dependencies and haskell dependency management, and does so in a reproducible manner at system level, it has become very popular among the correctness loving Haskell programers.

However it may be pointed out that although what nix does is impressive compared to stack it’s harder to use. The langauge nix langauge is peculiar, for example it has both a ;, and being reduced to a single expression. It has no type system but does full correctness checking before exucting. But it has a massive repository of examples.

Stack and nix

Stack provides the ability to specify system dependencies trough nix. Which is very useful as you now can let any developer regardless of Linux distribution, get on board with your stack project, without having to find out which specific system packages need to be installed. Is this combination the solution? Easy to use and being fully reproducible? Alas no this setup also has issues.

It has an opt in for the isolated builds nix provides, so stack would first look if a package is specified in the nix configuration, if not it would fall back on system libraries. This is rather strange, because you enable the plugin for reproducible builds, but the default behavior is to look for system libraries (eg be not reproducible). There is an opt out for this behavior (pure:true), but it seems more sensible to make this an opt in.

The reason why this behavior is undesired is because if one programmer starts using http-client-openssl, and happens to have openssl-devel installed on his system, then his colleague try to build the project, his build will fail. If pure:true was enabled the first developer would’ve noticed the issue and added it into the nix configuration.

However the way stack tells the user about the missing dependency is also peculiar. In case of the pure configuration, if stack can’t find the library, it will ask the user to install the dependency on his system. Which is of course pointless because one needs to add it to the nix configuration  Although the error message was intended to be helpful, in this particular case it ends up sending the user in the wrong direction.

Although the error message was intended to be helpful, in this particular case it ends up sending the user in the wrong direction.

Git and stack

Stack’s power lies in that it makes it easy to do the common things. For example creating a library for github is trivial. Stack helps by allowing users to specify a ‘github’ field in the package.yaml file, which will generate an url to both the source and the issue tracker on github.

name: voicebase

version: 0.1.0.0

license: BSD3

author: "Jappie Klooster"

maintainer: "jappie.klooster@daisee.com"

copyright: "Daisee"

github: blah/blah

Now although github is extremely popular in opensource it’s of course not the only choice, One may put it on a different host, such as bitbucket, or host their own source code with gitlab.

There is no doubt that stack supports specifying an alternative, however it is unclear how to replace the github field properly with alternatives. The assumption was that the gihtub field was just a shorthand to fill in some other fields. It is hard to find what it does because it’s an odly specific question, but it turns out that hpack is used to parse the package.yaml file. Perhaps the git field is used to replace github? It is unclear. It’s also ironic in that we can immediatly observe the difference strong types make in documentation ability, this yaml file is not strongly typed.

Commit dependencies

In certain situations one may need to change a library. The typical way of doing this is to make a github fork, and then specify in the dependency manager, that a specific (git) url needs to be used on a specific commit hash. For example: If one tries to get the 56e833 commit from the voicebase library, you should record the hash and url somewhere.

If we google for the query stack.yaml git dependency, you just need to know that you configure this in stack.yaml, which is completely unrelated to package.yaml google points you to an outdated doc page which fails to work. A helping stackoverflow gives the reason why it doesn’t work, the syntax recently has changed and Google hasn’t updated yet. One can hardly blame stacks maintainers for this of course. But it still impacts a users’ experience.

Conclusion

Dependency management in Haskell is complicated. Even if one is able to become productive in the langauge, any of the problems described here could still make it difficult enough for them to give up on the system they want to build. Learning about functors and applicative is fun, learning what specific syntax to use to make stack pull in a git repository is not.

![[]](https://jappieklooster.nl/theme/images/category-tools.svg)

![[]](https://jappieklooster.nl/theme/images/category-reflection.svg) Haskell 💜 Vibes

Haskell 💜 Vibes

![[]](https://jappieklooster.nl/theme/images/category-technique.svg) Death💀 to type classes

Death💀 to type classes

![[]](https://jappieklooster.nl/theme/images/category-story.svg) Private repository flake input

Private repository flake input